by Jenny McGarvey, Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay

There is a cautionary tale you hear all too often in environmental planning. An organization visits a neighborhood, identifies an opportunity to build public green space, plants rows of trees, but a year later, many of the saplings die and the residents are left with nothing but sticks.

Whenever this happens, not only are time and resources wasted, but the community members often become stubbornly against any future tree plantings—and understandable so.

Engaging a community before and after trees are planted is a difficult task, but an urban forestry collaborative working in the Carver neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia offers a solution. Here, community members weren’t just the recipients of new trees, but partners providing input and buy-in every step of the way.

“Tree Inequity” in Richmond, Virginia

Located in the heart of Richmond, the Carver neighborhood straddles the boundary between downtown and the city’s northside, surrounded by the campuses of Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) and Virginia Union University. Originally settled by German- and Jewish-American immigrants in the 1840s, Carver transitioned to a prosperous African American community in the early 1900s. Today, the historic neighborhood continues to be a predominantly black, working class community.

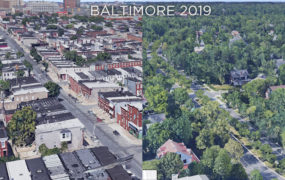

In the 1930s, the Carver neighborhood was subjected to a now-illegal practice – today referred to as redlining – where in which financial institutions withheld loans and other services based on location versus individual qualifications. Redlined neighborhoods were predominantly low-income and communities of color. The impacts of this racially discriminatory housing practice are well-documented, still exist today and include environmental detriments. Research shows people who live in neighborhoods with fewer trees and limited access to parks and green spaces may experience more heat-related illnesses and death, poorer air quality and more associated respiratory diseases, like asthma, decreased physical activity leading to increased obesity and reduced psychological health. This uneven distribution of trees along socioeconomic lines results in “tree inequity,” where trees and their benefits are not spread equally across cities. Nationwide, redlined neighborhoods have on average 23% tree canopy cover, compared to 43% in “greenlined” neighborhoods that are characterized by U.S.-born, White populations with newer housing units.

In November 2017, VCU’s Office of Sustainability initiated a pilot project to collaborate with campus-adjacent neighborhoods to create greener and more walkable spaces. This project is known as the Richmond Urban Forestry Collaborative (Collaborative), funded in part by the U.S. Forest Service’s Urban & Community Forestry Program. During the first year of the Collaborative, VCU students inventoried every tree within the Carver neighborhood, including standing trees and vacant tree wells (the indented area where roots once were). They also conducted several spatial analyses using aerial imagery and geographic information system tools to understand the existing tree canopy cover in the city of Richmond. According to Wyatt Carpenter, project lead and sustainability projects and program coordinator in the VCU Office of Sustainability, Carver had less than 10% tree canopy cover, compared to a city wide average of 26%. “Carver had among the lowest tree canopy cover of all neighborhoods in the city of Richmond,” said Carpenter.

Getting community input, door-to-door

While VCU students were conducting the neighborhood tree inventory, Carpenter focused on generating buy-in from the Carver community to increase the neighborhood’s tree canopy. Successful community engagement relies on community members identifying their own needs and expectations and advocating for them, providing a shared sense of ownership by residents and the project team. Community members are invested in the project outcomes, and above all, feel that they have been heard and included as partners throughout the planning process. This process can begin with building a coalition of support around community leaders.

For Carpenter, that meant gaining buy-in first from the Carver Area Civic Improvement League (CACIL). CACIL was founded in the 1950s and serves to, “bring neighbors together to address issues of housing, public improvements, land use, litter control and planning the neighborhood’s future.” Connecting over a shared goal to make Carver a better place to live, work and visit, CACIL and Carpenter agreed to work together to engage the rest of the neighborhood on the environmental, economic and health benefits of trees.

The Collaborative organized an urban forestry symposium for project partners and residents to learn about the role trees play in cities. Speakers included Casey Trees and faculty from the City University of New York. These experts gave presentations and answered questions on urban forests. Local non-profit Capital Trees led a tour of the Low Line Park, an example of a recent, large-scale green space project in the city, and CACIL President, Jerome Legions, Jr., guided attendees in a walking tour of Carver.

Through the symposium, CACIL meetings and one-on-one conversations, common concerns were voiced by residents about the new trees. There were questions of long-term maintenance (who would guarantee the trees were pruned and well-cared for?) as well as short-term implementation (who would water the trees in the first few crucial years of establishment?) These concerns stemmed from community members witnessing other failed projects, and an understaffed city urban forestry program lacking the capacity to water and regularly check-in on each tree themselves.

Addressing these concerns, Carpenter established a student summer internship program in which VCU student interns visit and water each sapling during the hottest months of the year, as well as weed and collect trash in and around the tree wells, and keep track of general plant health. A select few students also became trained as Richmond Tree Stewards, gaining the skills and experience to do structural pruning.

The Carver tree inventory identified 190 empty tree wells on city property. Carpenter then worked with the Virginia Department of Forestry and Richmond Tree Stewards to assess each tree well to figure out which ones could be planted in; for example, some had clearance issues for power lines or alleys. Of the remaining list, Carpenter and VCU students went door-to-door, asking each resident who lived in front of a potential planting site whether they wanted a tree, and if so, what their specific interests and needs were, in order to pick the optimal tree for them from the city’s approved tree list.

Ultimately, 70 spots for trees were identified, and 62 trees paid for by the Virginia Department of Forestry were planted in November 2018, one full year after the planning process had begun. Thanks to consistent care by VCU students, as of summer 2020, only three trees have died; one lost to a utility pole, another cut down, and an apple tree that died of natural causes.

Next steps for the Collaborative

The Collaborative is now expanding its work to other neighborhoods in the city. This fall, VCU partnered with the Enrichmond Foundation to plant trees at Amelia Street School. Once again, they are working alongside local groups, this time the Randolph Neighborhood Association, the Mamont Foundation, as well as the Virginia Department of Forestry. VCU will also conduct a full inventory in 2021 of the Carver project to see how well the trees are doing, and to gain early numeric estimates of tree benefits, such as increased shade and reduced heat.

The Carver project and other tree planting efforts like it work towards the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Tree Canopy outcome, which aims to expand urban tree canopy by 2,400 acres by 2025.