Story from Vibrant Cities Lab, used with permission

Context

In 2007, a city-wide assessment showed a worrying lack of adequate canopy cover in Baltimore, also known as Charm City. This prompted the creation of a tree planting initiative, TreeBaltimore, with the stated goal of achieving 40% tree canopy cover – a 13% increase – by 2037. Instead of expecting city agencies to do all this work alone, TreeBaltimore provided technical assistance, capacity building, and standards and protocol guidance to grassroots organizations. The result is a supportive network of organizations working within a range of niches that were able to expand operations efficiently and expeditiously.

Baltimore Tree Trust (BTT) significantly benefitted from this support during its start-up phase, from its founding in 2008 to when it was fully operational in 2012. In addition to assistance in identifying what areas of Baltimore to concentrate on first, BTT also learned how to navigate already established municipal protocols, identify what work required permits, and embrace different strategies for seeking support for planting on private property versus on public property.

Think City-wide, Act Hyper-local

Although BTT is now the city’s lead tree planting partner, in its first year, the group only got 50 trees in the ground. With a model relying mainly on word of mouth, this grassroots organization concentrated its efforts on one high priority, low tree canopy neighborhood at a time, with an important new support feature: helping to maintain the trees a full two years after planting to drastically increase survival rates. This proved to be a turning point, not just in a city-wide strategy of increasing tree canopy, but also in building community trust. Before the organization was founded, most new plantings were not maintained, and more often than not, contributed to urban blight rather than alleviating it.

Today, BTT has planted 9,500 trees. By slowly ramping up the scale of their plantings, they were able to intersperse tree plantings with more informal events that elevated resident-led conversations about trees. As the organization grew and became more established, it gained input from residents on community forestry plans. Within a few years, BTT was able to substantially increase tree canopy cover in seven neighborhoods in the Harris Creek Watershed in East Baltimore, an area that previously had the lowest tree canopy cover in the city.

As with any community, there were a few members who were not supportive of tree planting efforts, citing concerns about maintenance as well as some based on misinformation about increased crime, vermin, and tree roots causing sewer pipe damage. But, interestingly, some residents who were not wholly supportive of BTT’s efforts would still ask if the organization was hiring.

BTT had already partnered with the non-profit Center for Urban Families to hire neighbors living near planting sites as seasonal workers, and at the end of the season, the recent hires would enter the talent pool to often join other tree care contractors for short-term work. By engaging with the community early on in their planting and planning efforts, BTT realized how they could further leverage their greening work into a workforce development program. They turned the spring/fall day-laborer hiring initiative into the Urban Roots Apprenticeship. When the organization went door to door talking about the jobs available in forestry, it changed most people’s perceptions about their work and the multiple roles the urban forest can play to enhance the quality of life in a neighborhood.

Since 2013, The Baltimore Tree Trust’s Urban Roots Apprenticeship program trained, mentored, and connected marginalized Baltimoreans to careers in urban forestry and landscaping. Through a more formalized partnership with Center for Urban Families’ STRIVE Program, BTT identified career ready candidates, paired candidates with mentors, and provided a 6-week long paid skills training. Currently, Bryant Smith, BTT’s new executive director, and Justin Bowers, BTT’s director of programs, are working diligently to simultaneously re-envision and expand the organization’s workforce development curriculum. “It’s going to be open entry, open exit, with a core curricula that then leads to direct pathways [into the] field. We want to highlight the diversity of positions in the urban forestry field,” explains Smith. “This new model will allow us to spend more time with folks, and craft pathways to match the specific needs and interests of each participant. For instance, if someone is more tech-savvy, we will put them in a technology or GIS-based pathway. That’s a big change from what we were doing before.”

“Essentially, we want to prove that the tree care and landscape industry can provide more than just a job — it can be a lifelong, fulfilling, and lucrative career.”

Be the Change You Want to See

BTT is one of many white-founded urban forestry non-profits that operate in cities whose populations are largely of color. It is also not unique in its struggle to address diversity and equity, not only in its volunteer base, which is largely white, but in its staff and board. At first, the board faced an uphill struggle in remaking their organization to be reflective of the neighborhoods they work in – but they are rising to the challenge.

In addition to hiring more Black associates, they have brought on and promoted Black Baltimoreans into leadership and managerial positions, including two consecutive Black executive directors. “This is a motivator for Black folks, not just to participate in training programs for entry level positions, but to show that there is a ladder one can climb, even up to an executive level,” says Smith.

Still, Smith would love to see more diversity in their workforce development program participants. “We want cohorts that span a greater diversity of ages and genders,” he says. As one of the few person of color-led urban forestry organizations in the country, Smith is striving for BTT to be a shining example of what’s possible.

Lessons Learned

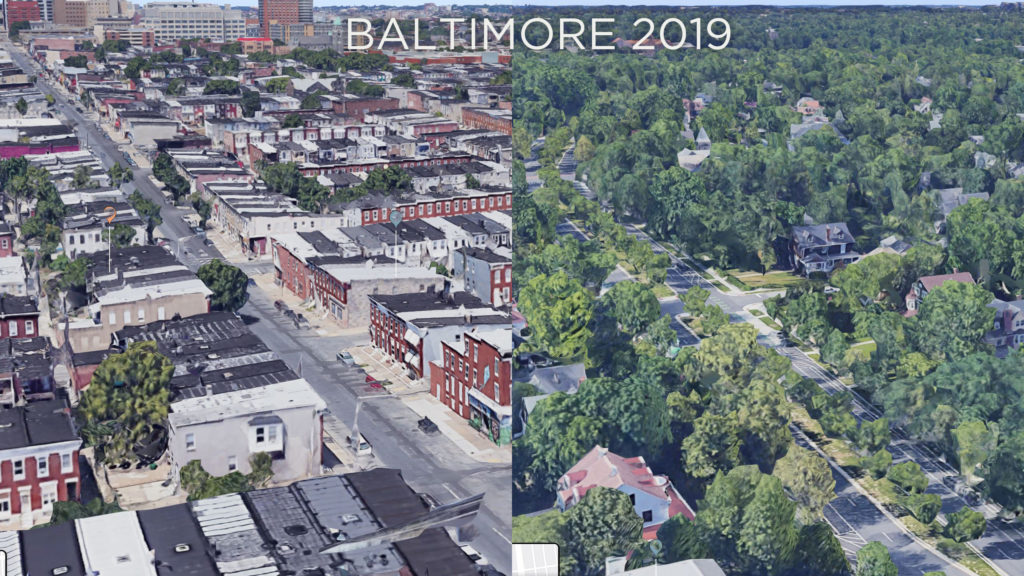

Baltimore still has a long way to go to achieve a 40% tree canopy, and growing tree canopy in Maryland’s largest city by land area (with 80 square miles) and population (620,000 people) is not easy. Some days the effort seems to be analogous to taking three steps forward and two steps back: from 2007-2015 they gained 4% canopy, but lost 3% due to factors such as disease, storms and development. Yet this one percent net gain equates to an additional 200 acres of tree coverage for the city, and with it, an increase in benefits, such as a reduction in utility bills and stormwater runoff. BTT’s vision is to put 10,000 new trees in the ground every year, while simultaneously creating a pipeline of diverse urban forestry workers diverse urban forestry workers who are ready to care for and maintain these trees for a living wage.

But with a variety of social and financial issues competing for Baltimoreans’ time and attention, greater public awareness around trees could be the key in accelerating planting efforts in Charm City. Charles Murphy, a manager at TreeBaltimore, remembers when former Mayor Shelia Dixon would bike the city to help deliver trees for community tree planting events. He thinks more engagement with city officials, including council members, could help make trees a more prominent part of the public discourse. Charles sees hope in a new, diverse generation of public leaders. A recent election changed the composition of the City Council resulting in seven of Baltimore’s fourteen council members being under the age of 40. Here’s hoping they find trees charming.

Credits

- Growing Tree Canopy through Environmental Justice Project

- This case study is one of five developed as one component of the 3-year Growing Tree Canopy through Environmental Justice Project. The project was funded by a grant from the USDA Forest Service to the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments. This organization is an equal opportunity provider. Project partners include the District of Columbia Urban Forestry Division, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Prince George’s County Department of Environment, and American Forests.