Post-industrial cities face a suite of interconnected problems. Reusing urban wood can be viewed as a systems solution to a complex problem – a means by which to begin to renew and revitalize lives and communities as well. Photo courtesy of USDA Forest Service.

Story by Sarah Hines, USDA Forest Service

Among some of society’s most complex and interconnected challenges – unemployment, ecological degradation, communities fractured by lack of opportunity and incarceration – it’s understandable if you didn’t realize that wood waste is also problem (though it’s likely that this audience is already more familiar than most with urban wood waste issues!). Yet the “problem” of urban wood waste, when viewed differently, can become a remarkable nexus for addressing such complex challenges.

Wood accounts for more than 10% of the annual waste material in the U.S.; in 2000, more tree and woody residue was generated from urban areas than was harvested from National Forests. And this waste creates costs – for municipalities, businesses, and landfills that pay for its hauling and disposal. But by far the biggest losses associated with urban wood accrue in the form of missed opportunities. By rethinking the use and disposal of urban wood, cities and businesses can generate profits, reduce costs, and develop new revenue streams. But such efforts require multi-sector collaboration, innovation, and trust. Viewed as part of a complex system, urban wood can become a conduit for tackling a complex landscape of social, environmental, and economic problems. In Baltimore as in many other cities, this complex landscape of problems includes:

- Substantial unemployment and poverty, approaching 30% in some neighborhoods; unofficial estimates may be higher.

- Thousands of vacant and abandoned buildings that create blight, depress neighborhood values and safety, and serve as hotspots for illegal activity, trash accumulation, and rodent problems.

- Substantial incarceration, approaching 3% of the population in some communities; Baltimore City residents comprise 10% of Maryland’s population but 33% of its prison population.

Low tree canopy cover in some of the most challenged neighborhoods, compounding issues related to the urban heat island, stormwater runoff, and other public health issues.

Legacies of social and racial injustice, including persistent effects from Redlining and other discriminatory housing practices and public policies.

The Dirt on Wood

Wood waste generally comes in two forms: fresh-cut wood—which consists of felled or fallen trees that had been growing in a community; and wood from deconstruction—that which can be reclaimed from abandoned homes and buildings. Post-industrial cities throughout America generally have underutilized supplies of each.

In most communities, when a tree does or must come down due to a storm, decay, disease, or construction, it’s treated more or less as a waste product, not timber. The trunk and significant branches are cut into small lengths for ease of handling and disposal. The rest is chipped. These components may have a second life, in the form of low-value mulch or firewood, or they may simply be dumped – either way, their handling and disposal is typically a cost and liability. Few operations currently have infrastructure or processes to consider each tree’s value and process it accordingly. Yet according to research done by the USDA Forest Service, reclaiming fresh-cut wood alone from the national waste stream could supply 30% of the annual consumption of hardwood trees in the country. Diverting wood from the waste stream preserves valuable material, reduces landfill crowding, and creates hyper-local and charismatic materials for architectural and furniture design and more. Having systems in place that can effectively put large pulses of fresh-cut wood to use will be ever more critical as cities face more extreme weather events from climate change and pests and pathogens from globalization.

In addition to this fresh-cut supply, many cities have unrecognized treasure in the form of old growth timber that is currently locked up in vacant, abandoned, and crumbling homes and buildings. In Baltimore alone, there are officially 16,000 vacant and abandoned buildings, but unofficial estimates suggest this number could be as high as 40,000. Many of these buildings were built over a century ago using virgin- or second-growth wood of native eastern deciduous forests with trees that were often 300-500 years old when they were cut down. In Baltimore, virgin southern yellow pine was used to build the joists and flooring in the majority of homes. This old-growth wood is “extinct” in the modern sense, as fewer than 0.01% of old growth southern pine forests still exist, and those that do will not be harvested for timber. Wood from these trees is of a size and quality that is not possible today, when trees are grown faster and on shorter rotations. It is denser, stronger, and more resistant to rot and termites – but primarily, it is gorgeous and rare. In addition, the century-old brick of the rowhomes can be its own unique treasure – possessing quality, character, and heterogeneity that proves rare today. And yet cities have been wasting this resource – demolishing homes and sending tons of rubble to the landfill. All the while, too many neighborhood residents sit by idly, unable to find employment, watching as these 2-3 crew demolition operations proceed.

Developing and Financing an Urban Wood Economy

Developing an Urban Wood Economy requires recognizing the following:

- Considering the highest and best use of fresh cut wood can generate greater value at the end of a tree’s lifespan, creating cradle-to-cradle opportunities for re-investment in urban forestry.

- Deconstruction can create 6-8 times more jobs than demolition.

- Deconstruction and some urban wood sort yard jobs are well-suited to those with barriers to employment, like low education or previous incarceration.

- Employing people with barriers to employment, and providing an on-ramp to a career, can create positive feedback loops in communities, reduce government costs, and increase government revenues. Of particular note is the importance of these programs to address the high cost of incarceration and recidivism.

- Urban wood generation, whether from fresh cut or deconstructed sources, complements, rather than competes, with rural wood generation. The products from urban wood are unique and different from traditional timber products, and can help support the U.S. wood industry.

- The most viable partnerships require the participation of multiple partners; public-private partnerships have been foundational to the success of urban wood efforts in Baltimore.

The Baltimore Urban Wood Framework

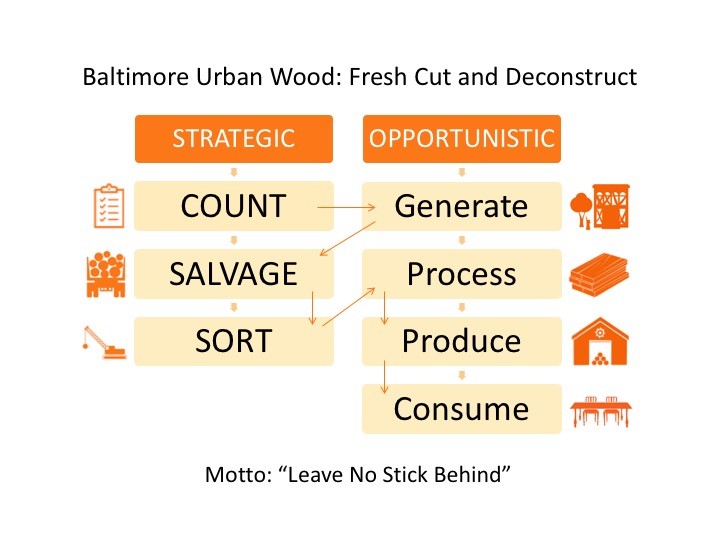

Working withpartners such as Humanim and the Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks, the USDA Forest Service has developed a framework for urban wood utilization that can support development of urban wood economies. The generation of wood waste material, and its disposal or reuse, can happen opportunistically or strategically. If it is viewed as a byproduct of an activity, it will likely be handled opportunistically. That is, it will be disposed of in a path of least resistance with minimum effort, often with the materials going to a landfill or, in the case of fresh cut wood, with the material being chipped into mulch. Alternatively, if it is viewed as part of a reuse process, it may be salvaged, sorted, and aggregated to sufficient scales that provide an opportunity for various wood markets.

Rethinking Waste

“Waste is a verb, not a noun.” This is a phrase worth remembering when it comes to urban wood. As we explored in our first post, urban wood is part of a complex system with linkages to a suite of social, economic, and environmental issues. Solving complex problems requires a systems type of solution. Developing an urban wood economy means examining the complexity of a wide-ranging socio-economic-environmental system and trying to recognize challenges as opportunities; trying to identify the points in the system where “waste” exists and recognizing that we can turn this waste into other verbs – reusing, renewing, revitalizing – wood, lives, and communities. This becomes ever more possible when we move beyond considering only what’s in our own domain, and partner across sectors and domains – we can begin to recognize opportunities for employment, revenues, avoided costs, and ecological restoration. A socially innovative approach to urban wood embodies three core components:

- Generating social and/or environmental impact, with the goal of achieving both

- Using socially responsible methods

- Pioneering a financially sustainable approach

Achieving this trifecta often takes collaboration among diverse, non-traditional stakeholders and a systems approach. Often, public-private partnerships and innovative financing approaches are critical in achieving financial viability; employing those with barriers to employment requires extra investment to ensure success, and this is an area where the public sector can help. In Baltimore, the urban wood economy is being driven by the coordinated efforts of city, state, and federal government agencies, social enterprise organizations, and the private sector, specifically:

- Humanim, a workforce development social enterprise committed to developing job opportunities for people with barriers to employment. Specifically, Humanim’s Details Deconstruction and Brick + Board are two flagship social enterprises that have created employment for hundreds of people.

- The City of Baltimore’s Departments of Housing & Community Development and Recreation & Parks, and Office of Sustainability, each of which has demonstrated incredible innovation and leadership in transforming waste to wealth

- The State of Maryland’s Department of Housing & Community Development, which embraced holistic metrics for success to support and enable innovation

Exploring Sustainable Supply Chains: Room & Board

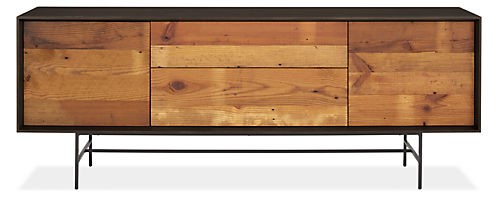

The McKean Media Cabinet – one of the many products produced under the banner of “Urban Wood Project: Baltimore” by home furnishings company Room & Board. Photo courtesy of Room & Board.

Fortifying the urban wood economy in Baltimore and replicating success in other cities becomes easier with a national partner who is willing to buy wood from multiple locations and has a national level impact. One of the ways that we have begun scaling is through a partnership with Room & Board, a modern furniture and home decor retailer committed to sustainable practices and American craftsmanship. Over 90% of Room & Board’s products are made in America using quality U.S. and imported materials. The company prides itself on its long-standing partnerships with family-owned businesses to create products with the best craftsmanship and lowest environmental impact. Interested to work with any organizations that have an interest in re-using urban wood, the Forest Service began discussing a potential partnership with Room & Board in early 2017. The company was intrigued by the story of the deconstructed wood and the social and environmental good it was enabling. Impressed with the reliable supply chain we had already collectively built, Room & Board sought to repurpose the wood. By 2018, Room & Board had sourced deconstructed wood from Brick + Board and launched almost a dozen products made of reclaimed yellow pine under the branding “Urban Wood Project: Baltimore.” The inclusion of “:Baltimore” in the brand implicitly allows for the development of urban wood products from other cities – and expansion cities and products are currently in development. Beyond this, urban wood is not proprietary to Room & Board. Indeed, our constellation of partners is seeks to work with others who share our vision of building a sustainable supply of and public demand for, and awareness of, urban wood.

Exploring Sustainable Financing: Social Impact Investing

Access to capital is another critical component to scaling and replicating the urban wood economy. Our work has explored social impact investing through a partnership with Quantified Ventures. A popular form of social impact investing is called pay-for-success financing. Pay-for-success is a method of funding a project, usually run by a government or nonprofit entity that will perform some social service. A key feature is that the project is evaluated holistically—by revenues generated as well as costs avoided. We have generated publically-available reports on the use of sustainable financing, in some cases Pay-for-Success financing, to scale up both deconstruct and fresh-cut urban wood operations. Central to all efforts is creating as many living wage jobs as possible for those with barriers to employment.

From Pilot Effort to National Success

Expanding scale and scope is a top priority. Baltimore has been the pilot city, but we seek to share, replicate, and refine the urban wood economy model in any other city with interest. To that end, we host an annual Urban Wood Academy, a multi-day experiential workshop designed to share best practices and lessons learned around building a networked, regional wood economy. The Academy brings together diverse practitioners from various sectors, geographies, and backgrounds to engage in mutual learning with the Forest Service, Humanim, and City of Baltimore, and each other. The Academy is designed to facilitate two-way dialogue, uncovering powerful lessons in how a networked, regional wood economy may be implemented in different communities, and how these networks may tier toward a national urban wood economy.

Recognizing waste, as a verb, in all its many forms – resources, pollution, human potential — is central to any effort to repurpose urban wood. It’s about so much more than wood. It’s about systems level thinking and engaging systems-level actors across sectors. And like so many efforts to increase sustainability and resilience, successful efforts depend on working across boundaries – levels of government, sectors of the economy, seemingly disparate challenges – to produce innovative solutions. This kind of transformative approach leads to replicable, high-performance outcomes that improve lives, communities, and ecosystems.

For those interested in learning more, please visit the Baltimore Wood Project website and our sustainability teaching case, entitled “Reclaiming Wood, Lives, and Communities: How do we turn a waste stream into an asset that revitalizes cities?”